Bricks Without Straw? Mudbrick Construction in Ancient Egypt and the Biblical Exodus

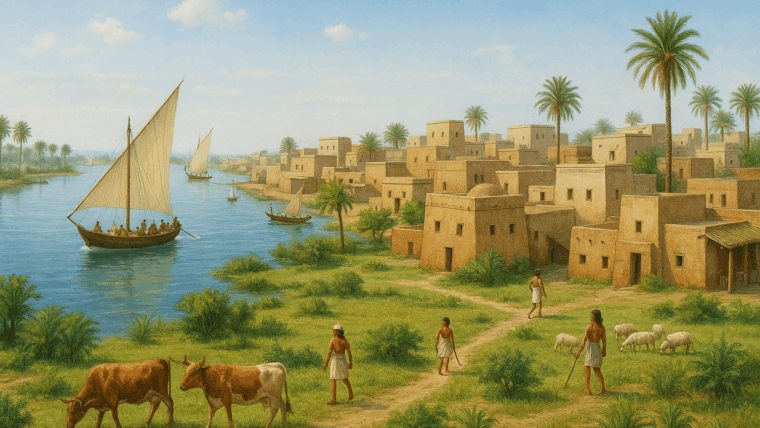

In the hot, dry lands of ancient Egypt, stone wasn’t the only building material of choice. In fact, most of the structures that supported daily life—from homes and palaces to granaries and temples—were not made of stone at all, but of something far more humble: mudbrick. For thousands of years, Egyptians shaped the Nile’s rich silt into bricks using molds, water, and a vital binding agent—chopped straw. This material not only made the bricks more durable but helped prevent cracking as they dried under the scorching Egyptian sun.

It’s here that archaeology and Scripture intersect in fascinating and affirming ways.

According to the biblical account in Exodus 5, the Israelites, while enslaved in Egypt, were forced to make mudbricks for Pharaoh’s construction projects. But when Moses confronted Pharaoh with God’s command to let His people go, the Egyptian ruler retaliated by intensifying their labor. He commanded that no straw be given to the Israelites, saying:

“You shall no longer give the people straw to make bricks as in the past; let them go and gather straw for themselves.” (Exodus 5:7, ESV)

This passage has often been misunderstood or misquoted. The Hebrews were not forced to make bricks without straw—doing so would have been counterproductive and structurally unsound. Rather, they were required to make the same quota of bricks without being provided straw, meaning they had to find and gather the necessary material themselves, dramatically increasing their workload.

This detail aligns perfectly with what we know from Egyptian mudbrick construction techniques. Ancient builders routinely mixed clay with straw to improve cohesion. Without it, the bricks would crumble and disintegrate. So, the text of Exodus is historically consistent—not an exaggeration or myth, but a real depiction of construction practice and punishment.

A Monument of Mudbrick: The Pyramid of Hawara

One striking archaeological example of large-scale mudbrick use is the Pyramid of Amenemhat III at Hawara, located near the Faiyum region. Dating to the Middle Kingdom (12th Dynasty), this structure is largely built of mudbrick, with only parts of the inner core and burial chamber encased in limestone. Amenemhat III is often identified as a possible Pharaoh during the time of Joseph—shortly after the Hebrew patriarch rose to prominence in Egypt (Genesis 41).

Joseph’s leadership during the seven years of famine is closely tied to Egypt’s storage infrastructure. Genesis 41:48 tells us that Joseph “stored up grain in great abundance,” which would have required massive storage facilities—likely made of mudbrick. The pyramid complex at Hawara includes remains of such granary systems, reinforcing the biblical account with physical evidence.

Fast-forward to the New Kingdom, particularly the 18th Dynasty, and we see Egyptian expansion in the Delta region where the cities of Pithom and Raamses were constructed—identified in Exodus 1:11 as storage cities built by the enslaved Hebrews. Excavations at Tell el-Retabeh (Pithom) and Qantir/Avaris (near the ancient city of Raamses) have revealed mudbrick storehouses and massive construction projects consistent with the type of forced labor described in the Bible.

Mudbrick as a Link Between the Text and the Terrain

Holding a mudbrick from Hawara in your hand, you’re gripping a piece of biblical-era history. These bricks connect the labor of everyday life in ancient Egypt with the drama of divine deliverance. They are the very substance of the Hebrew experience in bondage—molded with sweat, shaped under oppression, and yet remembered in Scripture with stunning accuracy.

What the Bible records and what archaeology reveals come together in these sunbaked bricks. They are not symbols of myth or metaphor, but markers of truth—testifying to the reliability of the biblical account and the resilience of a people who, even in slavery, clung to a greater promise.